On Manipur’s New ‘Phantom’ Government

From the Editor’s Desk

February 6, 2026

Manipur now has a new government, which on paper, signals the return of democratic rule after a one-year spell of President’s Rule. But in reality, the state remains deeply divided and only partially governed, with large sections of the population still excluded from its reach since a deadly and prolonged wave of violence began on May 3, 2023. The situation calls to mind the idea of a “phantom government,” a structure that holds office but cannot carry out the basic functions of governance.

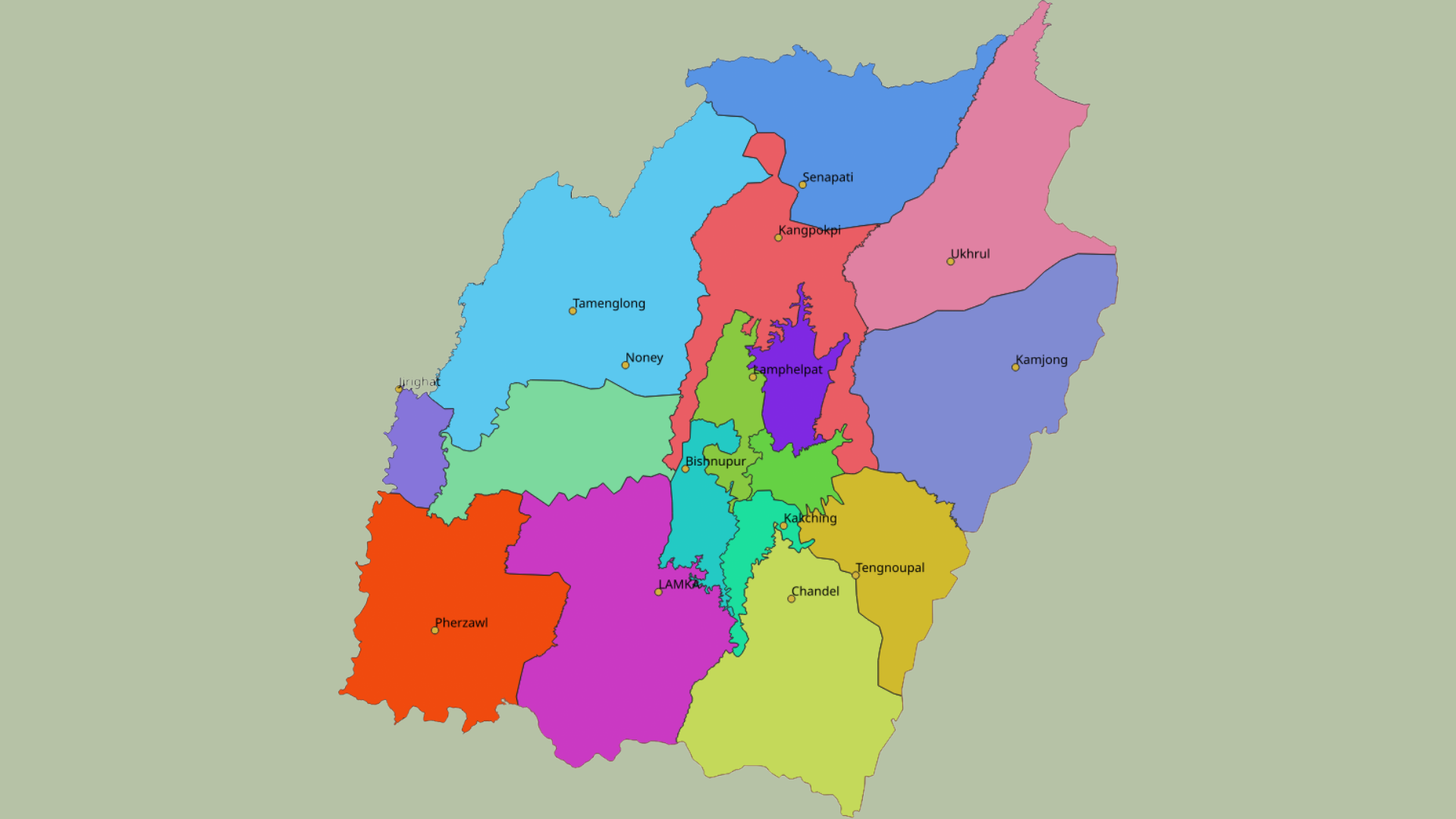

Since May 2023, Manipur has been engulfed in violence, involving the majority Meitei and minority Kuki-Zo tribal communities. The Meiteis mostly live in the Imphal Valley, while the Kuki-Zo groups live in the surrounding hills. What began as a protest over land rights turned into a cycle of ethnic killings, rape, arson and forced displacement. Since then, the state has remained physically and politically fractured.

President’s Rule was imposed in February 2025, following the resignation of Chief Minister N. Biren Singh of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), who has been named in a Supreme Court petition related to the “Manipur Tapes,” audio recordings that allegedly capture him admitting to involvement in the violence. About a year later, President’s Rule has been revoked following a formal claim to form the government by Yumnam Khemchand of the BJP, who sought permission from Governor Ajay Kumar Bhalla to establish a popular administration.

One wonders on what basis President’s Rule has been revoked. Merely because of Khemchand’s claim? But can the state machinery now also function in accordance with the Constitution?

To this day, most Kuki-Zo people cannot enter the capital, Imphal. Government officials, police officers and elected representatives from the community are unable to access the Secretariat, the High Court, or the Assembly where decisions are made. Ordinary citizens from the community cannot reach markets, schools or hospitals in the valley.

Two MLAs from the Kuki-Zo community are part of the new government, with one appointed Deputy Chief Minister. However, the Kuki-Zo legislators have faced widespread protests from their own community, with calls for a social boycott growing louder. This means they cannot claim to represent their community. And were they present in person for the swearing-in? They weren’t. Can Chief Minister Khemchand ensure their safety if they were to visit the legislative assembly? He can’t. Has the new CM made a plan to visit internally displaced people in Churachandpur or Kangpokpi? He hasn’t. He can’t.

If elected leaders cannot enter the capital, the head of the government cannot visit certain areas, and the police force is divided along ethnic lines, the situation meets the definition of a crisis of governability.

Yes, there has been a slight improvement in law and order, but in a context where hundreds of cases of violence remain uninvestigated and unpunished. This cannot be read as a return to normalcy. It simply reflects a pause in visible unrest, not the restoration of public confidence or institutional credibility.

Further, the intensity of violence has decreased, not necessarily due to improved policing, but simply because more than 33 months have passed since it began. No community can sustain prolonged periods of violence indefinitely. Yet the situation remains fragile, with the risk of renewed conflict, as none of the underlying causes have been addressed.

Without justice for those who were hacked or shot to death, the girls and women who were raped, and the families whose homes were destroyed, what is described as law and order is only managed silence. The failure to prosecute those responsible for killings, rapes and mass displacement leaves the system fragile and unreformed, with the same conditions that produced the violence still in place.

Even though a government exists, it does not have effective “state capacity,” which is the ability to carry out its decisions across all regions and communities. It holds office, passes orders and performs ceremonial duties, but cannot deliver services to all its citizens, enforce law and order across its territory, or ensure basic access to justice and representation. It remains part of the constitutional framework, but has little practical control over the political or administrative life of large sections of the population.

Until Manipur can restore access to governance for all communities, rebuild trust between citizens and institutions, and ensure that every person can enter their capital and be heard by their government, the return of an elected cabinet means little.

A phantom is something that appears real but lacks substance, which is why a phantom cannot govern.

You have just read a News Briefing, written by Newsreel Asia’s text editor, Vishal Arora, to cut through the noise and present a single story for the day that matters to you. We encourage you to read the News Briefing each day. Our objective is to help you become not just an informed citizen, but an engaged and responsible one.