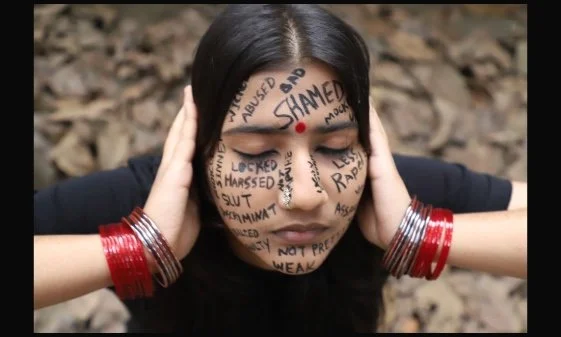

1 in 5 Women in India Experience Physical or Sexual Intimate Partner Violence

From the Editor’s Desk

February 18, 2026

A major study has found that although more than one in five women in India experience intimate partner violence each year, only a very small number of these cases appear in official records of police, health services, or support centres. The issue demands urgent action, as violence within the home causes immediate injury, long-term health harm, economic disruption, and effects that pass from one generation to the next.

A comparative study published in the March 2026 issue of The Lancet Global Health measures current need using past-year prevalence of physical or sexual intimate partner violence, based on Global Burden of Disease estimates, and compares this with administrative records from police, health, social welfare, and women’s centres across Brazil, Chile, Colombia, India, Italy, South Africa, Spain, and Uganda.

In this comparison, India and Uganda lie at the extreme end when prevalence of violence and official recognition are considered together. India’s past-year prevalence stands at 20.6%, with formal police reports reflecting only 0.1% of estimated need, while Uganda’s police records capture about 0.9% of estimated need. Spain, by contrast, reports a prevalence of 2.2% with police recognition reaching 29.8% of estimated need.

Women’s centres show wide differences in reach across countries. Services correspond to about 15.0% of estimated need in Spain, 14.8% in Chile, 4.2% in Italy, 3.0% in Brazil, 0.9% in South Africa, and 0.2% in India, while no national data are available for Colombia and Uganda.

India’s National Family Health Survey conducted between 2019 and 2021 shows that among women who experienced intimate partner violence in the previous 12 months, about one percent sought help from police and about 0.33 percent approached a doctor, even though 27 percent reported injuries. The survey also records social attitudes in which 45 percent of women and 44 percent of men considered wife beating justified under certain circumstances.

India’s high prevalence of intimate partner violence, combined with a wide recognition gap, points to violence that is socially organised. Such violence grows in environments where authority within marriage receives social approval and harm within the household is treated as a private matter rather than a violation of rights.

Household bargaining power – the leverage individuals hold to shape decisions, secure safety, or exit harmful relationships – forms another structural driver. Bargaining power strengthens through stable income, ability to go to a safe place in case of violence, supportive family networks, financial inclusion and credible state protection.

Institutional trust – the expectation that authorities respond with seriousness, speed, protection and fairness – is also a factor. Evidence cited in the study shows indifference within policing toward reports of severe partner violence against married women.

It also concerns state capacity, the ability of public systems to deliver services across the country through trained staff, reliable funding and coordination between departments. This capacity becomes visible in how widely services reach people, how effectively survivors are referred from one service to another, and whether data systems track the help they receive. India’s one-stop centres operate in districts across the country, yet they reach only a small share of affected women, and coordination between sectors responding to intimate partner violence remains limited.

An intersectoral national plan on violence against women is the most urgent requirement. Such a plan would bring together different parts of the government, including police, health services, social welfare and the justice system, under a single coordinated framework. It would clearly define responsibilities, timelines and shared indicators across ministries and states so that these institutions act in alignment rather than in isolation. Every country in the comparison except India had a national action plan in force as of 2024.

A clear and connected system for accessing care forms the second requirement. Survivors should be able to reach support through hospitals, clinics, women’s centres, helplines, or the police, and each point of contact should lead to referral and continued support rather than a single, isolated response.

Long-term change in social norms is also essential. Schools, community institutions and sustained public messaging influence attitudes toward violence and the willingness to seek help over time. Survey evidence from India shows that help-seeking declined between 2005 and 2021 even as recent prevalence increased, pointing to a growing gap between lived harm and the response of formal systems.

The scale of violence, combined with the limited reach of official response, makes the urgency impossible to ignore. A democratic state draws its legitimacy from its ability to protect people and deliver services, and violence within intimate relationships exposes the failure of that responsibility in everyday life.

You have just read a News Briefing, written by Newsreel Asia’s text editor, Vishal Arora, to cut through the noise and present a single story for the day that matters to you. We encourage you to read the News Briefing each day. Our objective is to help you become not just an informed citizen, but an engaged and responsible one.