Inside India’s Hidden Digital Market of Incest, Child Porn, Misogyny

A Disturbing Ecosystem Breeds a Generation of Boys Prone to Harmful Sexual Behaviour

September 19, 2025

On Sept. 10, an Instagram conversation with a young boy led me into a disturbing digital ecosystem where violent sexual content circulates freely. I now fear that a generation of boys may grow up normalising harmful sexual behaviour and misogyny.

I received a flurry of comments on one of my posts, one afternoon, which I first ignored. On social media, this usually means some random man trying to push into direct messages, if you’re a woman.

But one word caught my eye: “didi” (sister).

“Didi, please check your inbox. I have raised a very important issue,” the comment read. Curious, I opened my message requests. What I found wasn’t casual flirting or trolling, but a series of desperate, urgent pleas.

“I’m writing to you with a lot of hope. Please don’t break it,” read the first line. “I want to draw your attention to an extremely serious crime.”

And then another: “India is a place where we worship women as Goddess Durga and consider them the heart and soul of our families, but the same women become the victims of men’s perverted actions, sexual harassment and what not?”

The sender claimed he had witnessed online platforms openly circulating violent sexual content, from rape videos to clips of young girls, but warned that what he saw was only the beginning.

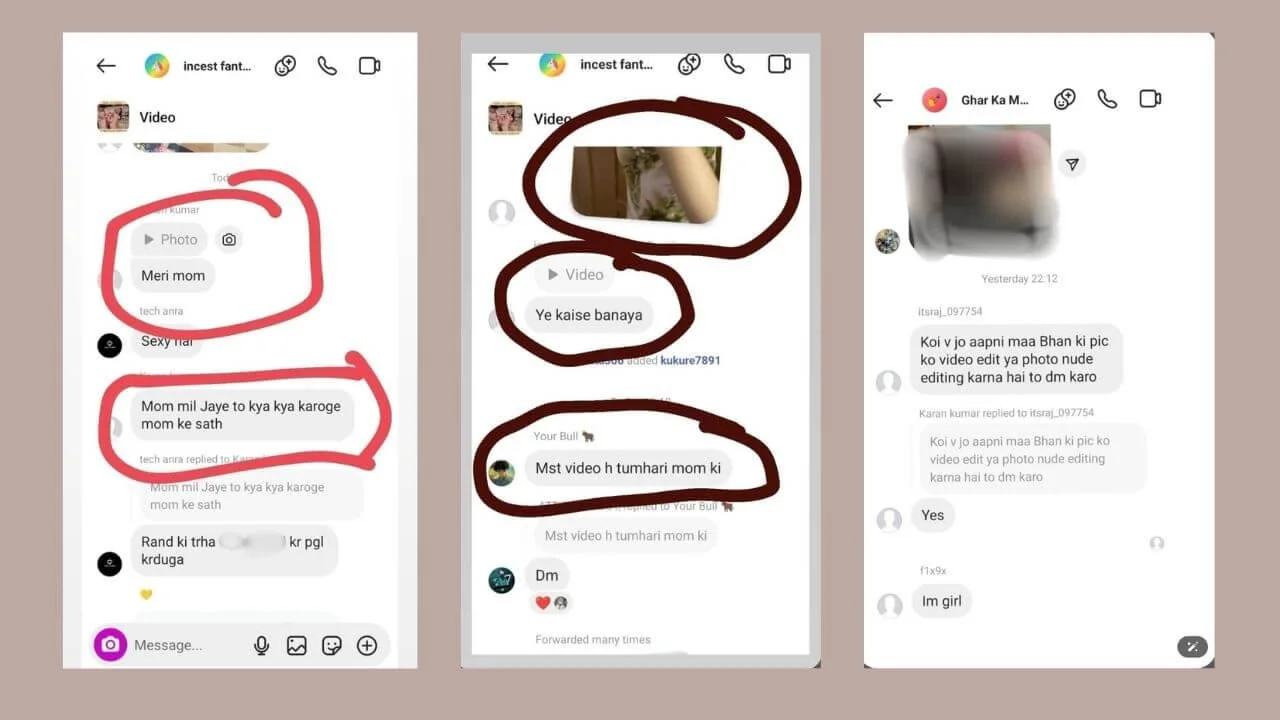

“Men on these platforms are sexualising their own mothers, sisters and friends and discussing how they would rape and sexually assault each other’s mothers, wives and sisters. They are also openly sharing child pornography and using AI tools to create deepfakes of women,” he wrote.

This was no longer just another DM. Whoever this was, he was terrified and determined to be heard.

He shared links to several Instagram accounts engaging in such content. One of them, “mom_hidden_clips,” contained photos and videos of mothers sleeping, undressing, or just sitting – pictures clicked from inappropriate angles. The idea seemed to sexualise mothers and encourage young boys to do the same.

A video posted on Sept. 11, 2025, shows a woman in her petticoat being filmed, probably by her son. In some videos, the women’s faces were hidden, while in others they were visible, with the camera focusing on specific body parts. Other accounts were named “Gharelu_masti_desii,” “mommytrollstelegu,” “family.is_lov.e,” “desi_hidden_clips_,” and so on.

(As of Sept. 19, several of these pages have been removed after Aman complained to Rati Foundation, an NGO that works to create safe spaces for children and women, both online and offline, to protect them from sexual violence.)

“They share secretly clicked pictures of their mothers, women in public places, public transport, restaurants, even hospitals,” he said. Going further, they ask for money in exchange for more depraved content.

I asked him who he was, and how he found me. “I’m an 18-year-old boy from Uttar Pradesh. I can’t go and complain to the police, but I found your account and thought you could help amplify this issue with the authorities,” he told me.

To protect his identity, I’ll call him Aman.

“They are all potential rapists, and they have no fear of law. I don’t know whose mother, sister, wife or daughter would become victims of such monsters. It’s disgusting to see thousands of men active over such platforms and groups, many of them teenagers. Such content promotes sexual violence and objectification of women. If we don’t stop this, the entire generation is going to normalise it. Please do something.”

Aman told me he is the only child of supportive parents. His father, an engineer, earns enough to provide for the family. But like many boys his age, the internet shaped him in unexpected ways.

“I started using smartphones in an extremely controlled manner in 7th grade. But starting Class 8, I was heavily using smartphones and the internet as classes went online after Covid. I was actively chatting, using YouTube and websites. I first looked for an obscene video over incognito mode on Chrome. Some days later, I was caught by my father. I left watching at that time but started again after some time.”

When I asked what drew him, he said, “The biggest factor is adolescence when sexual desires start kicking in for everyone. I used to use phrases like ‘naked girls’, ‘girls without clothes.’ Over time I learned the word ‘porn.’ I was addicted to it and watched it almost every day. I was regularly self-pleasuring myself, always in incognito mode on browsers.”

With time, he craved more. “When you watch porn on a regular basis, you start to crave something more interesting and more brutal. Gang videos, rougher stuff. I watched content titled ‘family sex’ and ‘teacher sex,’ but thankfully that never took over my mind. Still, my quest for more led me to other platforms.”

On Instagram, one reel triggered another. “I now realise that if someone watches even a little obscenity, then such things also start getting pushed into their feed,” Aman said. Through comments and bios advertising group links, he entered communities where boys shared screenshots of classmates’ stories and secretly filmed photos and videos of their mothers and sisters.

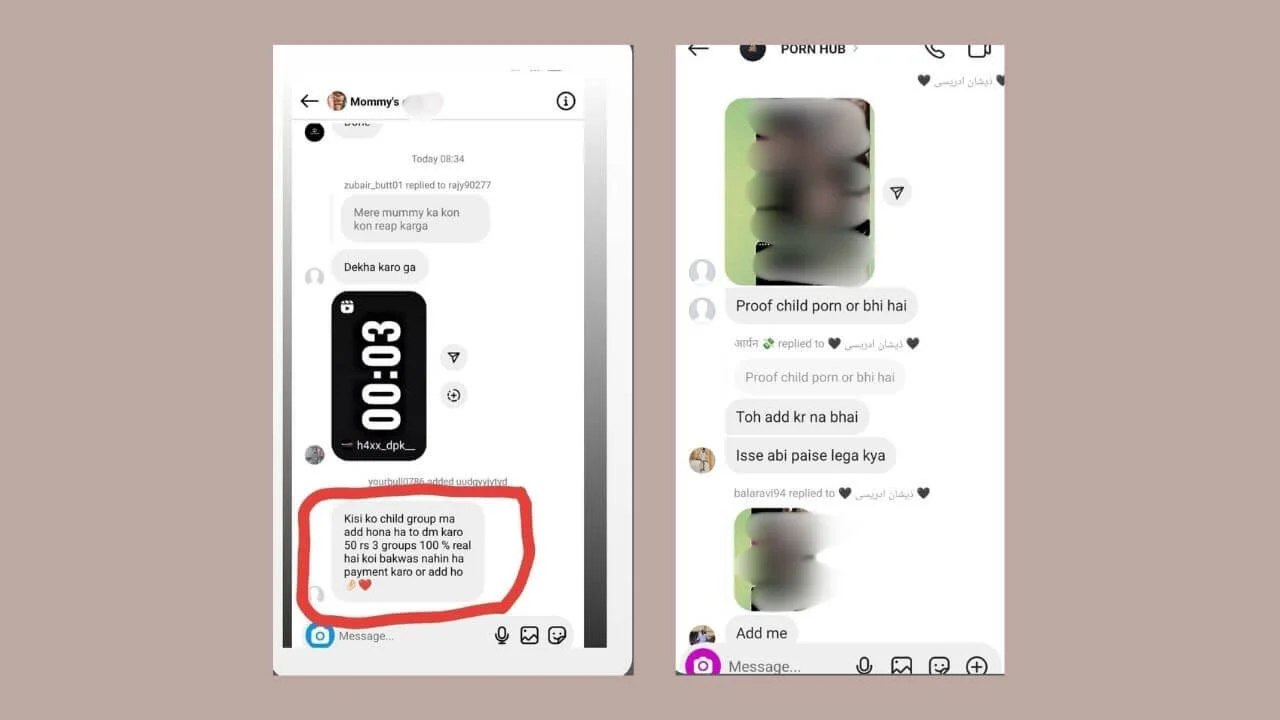

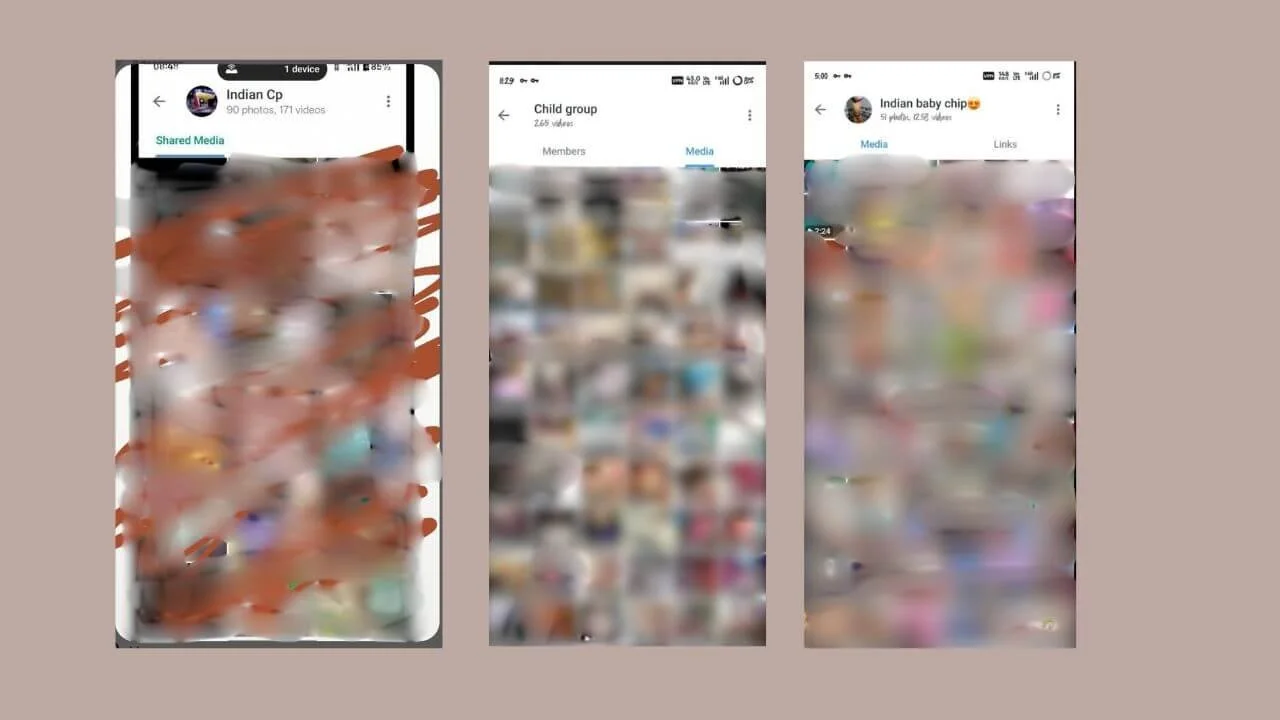

Soon, he found even darker groups. “One was called ‘sab apni mummy ki baat karo opnan.’ Others were called ‘bhabiyon ki jawaani,’ ‘my sweet lovely sister,’ ‘incest c****i.’ There are other groups sharing child pornography. Some even run on religious lines, promoting rape of women from Hindu and Muslim communities.”

Through Instagram, Aman reached Telegram and Reddit, which he calls “the biggest markets.” Within no time, he was part of more than 15 groups.

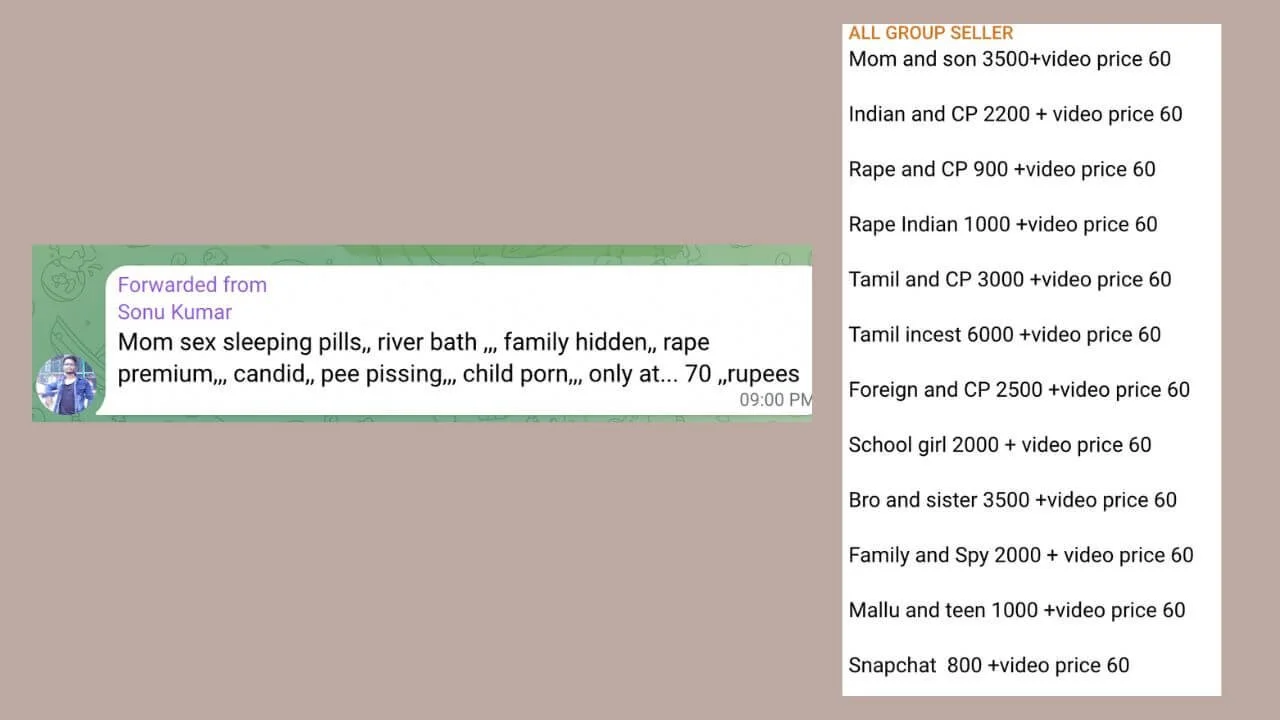

I joined several Telegram groups to verify his claims. These groups were ripe with everything from child sexual abuse content to real rape videos. A video showcased a small girl (about 10) being raped by a much older man, while she was unconscious. Another video depicted a boy (around 10) being abused by a much older woman. In all these groups, rape and child abuse content were the most sought after. One group, VIP আড্ডা গ্রুপ (VIP Adda group), had about 500 members. A pinned message read: “Brother sister real mon son rp (rape) forced Indian sleeping family spy all grups mega file low price DM fast.”

The users and content were also region-specific: Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu, Marathi, Bengali, and so on.

“There are hundreds and thousands of such groups operating across all platforms, without any check,” Aman warned. In his observation, most members were uneducated men from rural areas, including some labourers — though he also noticed a few educated people. There were also a few women on these platforms, probably sex workers, he said.

Aman began watching porn in Class 7. By Class 8, he was already disgusted when he saw a video of forced sex; that shocked him to the core. “Around that time, I was also watching Ramayana and decided I wanted to be disciplined. I stopped watching. But after a few weeks, I restarted. This is a loop that is difficult to break.”

Eventually, he said, he built “a wall in his brain” and began speaking out. But not everyone has that kind of self-control or family guidance to distinguish right from wrong. What they consume, they begin to believe is reality.

“If a 10-year-old or above is exposed to child porn and rape videos continuously for 3-4 years, and learns to sexualise his mother and sister, he will start seeing it as reality, the norm. He will objectify women and even children. Without guidance, with obscene content everywhere, young boys are vulnerable to addiction,” he warned.

A Disaster in the Making?

There is a growing wave of misogyny and violence against women worldwide, much of it fuelled by digital communities and social media platforms. Yet reporting on how this trend is unfolding in India remains sparse.

India today has nearly 800 million internet users – the second largest in the world after China – with about 491 million active on various social media platforms. Almost 69% of them are men. The average daily internet use jumped from less than an hour in 2019 to over six and a half hours in 2020 in India.

As the United Nations warns, these platforms are increasingly being used to spread anti-women rhetoric, reinforce discriminatory gender roles and incite real-world harm.

My interaction with Aman illustrates how social media, messaging apps and digital communities are fast becoming breeding grounds for real world harm against women. Adolescent boys exposed to such content risk not only having their worldview distorted but also becoming a real-world threat by acting on these thoughts. If boys are taught to sexualise the very mothers and sisters who shape their first lessons in love and respect, what hope is left for other women?

Unchecked, this ecosystem risks reducing women to nothing more than sexual objects in the eyes of young men. And such attitudes do not just endanger women, they corrode the foundations of society itself, creating unsafe environments where both women and men are victims.

Cyber psychologist and psychotherapist Nirali Bhatia explained that the biggest challenge with such behaviour is the extreme desensitisation it creates. “These boys lose all sense of rational empathy or respect—there are no boundaries. They don’t even see sexual abuse as sexual abuse, because they’ve become so desensitised. So, if someone tells them what you’re doing is wrong, they can’t relate to it. For them, the whole world already looks wrong, so how can their actions be questionable? This mindset breeds misogyny and violence. As they grow up, these boys face serious problems in their sexual lives and relationships—with respect, boundaries, trust, impulse control—because they’ve been conditioned to expect instant gratification.”

On one side lies unregulated violent sexual content, as Aman’s story reveals. On the other lies the “manosphere,” an umbrella term for online communities that glorify narrow, aggressive definitions of masculinity while spreading the false narrative that feminism and gender equality have come at the expense of men’s rights.

In these spaces, women are routinely portrayed as selfish, illogical or scheming, while men are cast as victims of contemporary society. This toxic mix of misogyny and male victimhood is used to justify harassment, coercive control and discriminatory behaviour.

The influence is global.

A 2023 poll by the U.K. charity Hope not Hate found that 80% of 16 and 17-year-old boys had consumed content created by Andrew Tate, the British-American kickboxer and self-proclaimed misogynist accused of rape, human trafficking and sexual assault. Another poll by Internet Matters revealed that 56% of young fathers under 35 approved of Tate’s views.

India has its own versions of Tate – homegrown influencers who churn out misogynistic rhetoric online and are increasingly popular among young boys and men. Their growing influence suggests we urgently need to examine how digital spaces are shaping gender attitudes in the country.

Accountability of Online Platforms

Online platforms must be held accountable for allowing such content to flourish. We regularly see how quickly companies comply with government orders to remove political posts, and yet when it comes to identifying openly sexual and violent material, their systems fail. Researchers have found that algorithms used by social media platforms are not only missing harmful content, but actively “amplifying extreme misogynistic content,” packaging it as entertainment.

The problem is not hard to find. A simple Google search led me to a website called Khanika’s Diary, which listed the “top five adult content pages” on Instagram, linking to a partner site called “Instagram Porn Id.” This shows how pervasive and easily accessible such material is. Several of my peers also confirmed to me that pornographic content circulates freely on Instagram, where group chats dedicated to such content are thriving.

Some platforms even permit pornography under specific conditions. Elon Musk’s X updated its adult content policy in May 2024 to allow consensually produced material, provided it is labelled correctly and not displayed prominently. Reddit also allows explicit content in certain subreddits. But neither has adequate safeguards against Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) or non-consensual deepfakes.

The most notorious of them all is Telegram.

A covert investigation by Hyderabad-based NGO Prajwala, led by activist Sunitha Krishnan, uncovered rampant CSAM circulation on Telegram. In just two weeks, investigators accessed 38 GB of content for 600 rupees, involving children as young as three, in groups with more than 30,000 members. Krishnan accused Telegram of enabling the trade by allowing pseudonyms, encrypted chats and massive groups, in clear violations of the POCSO (Protection of Children from Sexual Offences) Act, which makes it illegal to use a child for pornographic purposes, and punishes possession, storage or transmission of such material. Telegram only issued an automated response, with no official statement.

Grooming children to sexualise their own mother or sister, or encouraging rape, also amounts to sexual exploitation under the POCSO Act, which treats such conduct as harassment and abuse. It can also be seen as aiding and abetting potential sexual assault, since it normalises incest and rape in the child’s mind. If done online, it constitutes a serious offence under Section 67B of the IT Act.

Similar patterns appear abroad. In China, a group of more than 100,000 men was found sharing videos of women and children, including family members, without their consent. Despite China’s strict internet controls and regular crackdowns on pornography, Telegram’s encrypted channels enabled the content to spread. The platform is banned there.

Global pressure on Telegram is mounting. On Aug. 24, 2025, its founder Pavel Durov was detained at Le Bourget Airport in Paris. French authorities accused him of failing to cooperate with investigations into child pornography, drug trafficking, terrorism promotion and other crimes facilitated through his platform.

Meanwhile, platforms continue to shape the daily lives of young people.

From December 2025, Australia will ban under-16s from having social-media accounts. Platforms like Instagram, TikTok and Facebook will be required to block or deactivate underage accounts or face fines of up to AUD 50 million. The law shifts responsibility onto tech companies to protect children’s mental health.

Echoing this for India, cyber psychologist Bhatia said the internet’s appeal lies in its immense freedom but near-total lack of regulation. She argued that children under 18 should not have access to these unregulated spaces, noting that platforms such as Telegram and other social media add little value to their lives, and they would not miss out on anything essential.

India urgently needs to crack down on creators of abusive content, hold platforms and messaging apps like Telegram accountable, and provide safe counselling spaces for young people already caught in this trap.

You have just read a News Briefing by Newsreel Asia, written to cut through the noise and present a single story for the day that matters to you. Certain briefings, based on media reports, seek to keep readers informed about events across India, others offer a perspective rooted in humanitarian concerns and some provide our own exclusive reporting. We encourage you to read the News Briefing each day. Our objective is to help you become not just an informed citizen, but an engaged and responsible one.