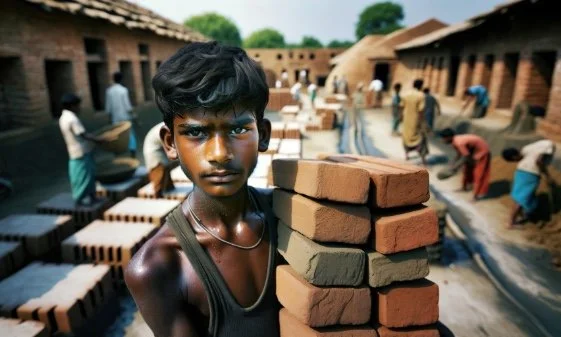

Bonded Labor Law Exists in India, But Millions Still Work in Servitude

Workers Denied FIRs, Compensation and Support, Says a New Report

November 29, 2025

India outlawed bonded labour nearly 50 years ago, but millions remain trapped in exploitative working conditions, according to a new report by a workers’ rights network, which has accused the government of neglecting its legal duty to enforce protections and support victims.

The National Campaign Committee for Eradication of Bonded Labour (NCCEBL) released its report in Delhi on November 28, citing widespread failure to enforce the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976. The group’s convener Nirmal Gorana said the law has failed to prevent forced labour, as officials often delay action or side with employers. The report says key enforcement steps like summary trials are rarely held.

The report, which presents data from surveys with 950 bonded labourers who had received official Release Certificates, concludes that the Act is routinely disregarded by district and state administrations across India, and that the Central Sector Scheme for the Rehabilitation of Bonded Labourers (2016) is failing in practice due to poor implementation, lack of coordination, and widespread denial of entitlements.

The report, shared with Newsreel Asia, finds that over 80 percent of workers surveyed never had a police case filed on their behalf. Filing a First Information Report (FIR) is a required first step under the law to validate the rescue, issue a Release Certificate, and initiate access to compensation and support.

Although the scheme promises rehabilitation and reintegration assistance of up to 200,000 (2 lakh) rupees, a majority of eligible workers never received even the basic interim aid promised at the time of rescue. Not a single male worker surveyed received the minimum amount of 100,000 (1 lakh) rupees they were eligible for. Only one woman received between more than 100,000 rupees, and nearly 54 percent of rescued children and 33 percent of women received nothing at all.

Beyond cash aid, the law also mandates non-cash support including housing, land, ration cards, caste certificates, school admission and health insurance. In practice, fewer than 2 percent of surveyed workers were given land, and less than 0.5 percent received skill development training. Over 85 percent were denied employment under the national rural job guarantee program (MNREGA), and nearly 70 percent lacked government-issued health cards.

The report links these implementation failures to a pattern of structural exclusion. All 950 workers surveyed belonged to Dalit, Adivasi or Other Backward Class communities. Scheduled Castes (Dalits) accounted for 63 percent, and nearly half the workers were women, many of whom reported sexual violence.

Despite caste-based threats and abuse, none of the cases had charges filed under the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, which is meant to offer enhanced protections against discrimination and violence. Field researchers found that statements of rescued workers were often recorded in the presence of employers or police, retraumatising victims.

Supreme Court lawyer Sanjay Parikh, speaking at the report launch, said the administration’s refusal to file FIRs rendered the Bonded Labour Act “just ink on paper.” Without this basic legal step, he said, no rehabilitation can begin.

According to the report, debt is often wrongly portrayed as the core feature of bondage, whereas in reality, unpaid wages far exceed the amount workers owe. On average, rescued labourers had debts of 5,283 rupees, but their employers owed them six times more in unpaid wages, averaging 32,514 rupees per worker. Not a single respondent had successfully recovered these wages through legal action.

Women and children remain particularly vulnerable.

Only 25 percent of rescued children were admitted to school, while more than a third were sent back into child labour after their rescue. For many families, the absence of education or work options meant that freedom was short-lived. The report states that rescue without follow-up results in re-bondage, especially in cases where workers are denied wages, housing, and food support.

The report shows that bonded labour persists in forms both old and new, across India’s agrarian and industrial economies. These include the Harwai system in Madhya Pradesh, where landless workers are forced to repay informal loans with lifelong farm work, and the Chakar Pratha system in Gujarat, which ties generations to inherited debt. In Odisha, barbers from marginalised castes are still expected to serve dominant caste families without pay, and in Maharashtra, entire families are locked into contracts in the sugarcane industry.

Though India has pledged to end forced labour by 2030 under the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the report says the government’s actions contradict that goal. Parliamentary data cited in the report shows that just 250 bonded labourers were rescued between April 2024 and January 2025, and that budget allocation for rehabilitation dropped from 51.5 million (5.15 crore) rupees in 2022–23 to 13 million (1.34 crore) rupees in 2023–24.

Legal precedents from the Indian Supreme Court, such as the Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India case of 1983, have defined any labour below minimum wage as forced labour, and presumed that debt-backed work is bonded. However, the report says many state and district officials continue to deny that bonded labour exists, and that members of Vigilance Committees, which are the bodies tasked with identifying and helping bonded labourers, are often employers themselves.

The NCCEBL urged the Indian government to formally acknowledge the continuing existence of bonded labour, enforce the 1976 law and implement the 2016 rehabilitation scheme in full, with proper documentation, legal follow-up and financial support.

You have just read a News Briefing by Newsreel Asia, written to cut through the noise and present a single story for the day that matters to you. Certain briefings, based on media reports, seek to keep readers informed about events across India, others offer a perspective rooted in humanitarian concerns and some provide our own exclusive reporting. We encourage you to read the News Briefing each day. Our objective is to help you become not just an informed citizen, but an engaged and responsible one.