LAGGED BEHIND | School Dropouts Among Tribal Children In Chhattisgarh

October 16, 2023

By Surabhi Singh

During my visit to Chhattisgarh state’s Sukma district, I was struck by breathtaking natural beauty and tranquillity and the captivating and unspoiled expressions of the residents. Women, adorned in knee-length, saree-like garments, signalled a departure from mainland India’s frenetic pace. Men displayed lean yet sturdy physiques, a testament to the rigours of tribal living. Meanwhile, children overflowed with joy and playfulness, greeting us warmly, albeit with a hint of reservation.

However, this beautiful landscape conceals a grim reality. Recent studies indicate that only 42% of Sukma’s population is literate. The area is predominantly inhabited by tribal communities, making up over 85% of the local population.

Across Chhattisgarh, the situation isn’t much better. Despite nearly 100% enrolment among primary-age children, a staggering 49.2% of tribal students in schools abandon their education by the end of elementary level.

This disheartening situation is what drew me to Sukma in the first place.

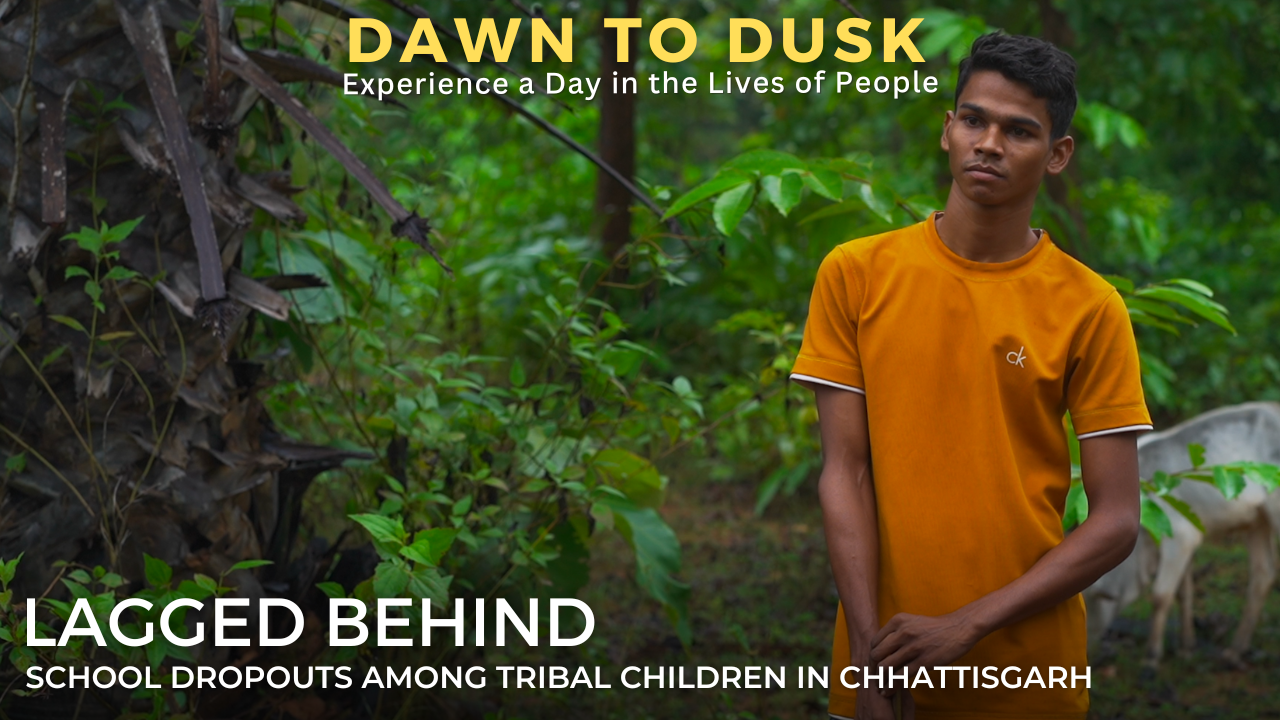

I had the privilege of meeting Mangal Markam, a 21-year-old from Turkapara village. I first spotted him labouring in the fields with his father and uncle. During a brief break, we struck up a conversation. Although intrigued by our presence and camera equipment, his shyness was palpable. When I asked if he knew about Delhi, he said, “I’ve read about Delhi in books.”

Mangal completed his 10th grade in 2017 before discontinuing his education. His textbooks still lay in his room. “I often sift through them,” Mangal said.

Apart from helping his family in the fields, Mangal operates a general store that stocks an array of items—biscuits, eggs, pens, toothbrushes, tobacco, and more. “There was no other work for me, so I started this shop,” he explained.

Mangal’s situation is hardly unique in his community. Nearly everyone his age in the village had also left school early. This trend is especially prevalent in the conflict-ridden southern districts of Chhattisgarh, including Bastar, Bijapur, Dantewada and Sukma. These areas are caught in the crossfire between the State and Maoist insurgents.

The average literacy rate in Chhattisgarh stands at 70.3%, but it plunges to 59.1% for Scheduled Tribes (ST). The situation is even more dire for ST females, with a literacy rate of just 48%. In the southern districts impacted by Left Wing Extremism (LWE), the literacy rate is 68.7%, compared to 74.0% in non-LWE districts.

The high dropout rate among tribal children in this region is influenced by a range of factors.

Culture

One of the key reasons we found, corroborated by various studies, is the pressure on children to contribute to the family income. Kids like Mangal often juggle agricultural labour with their education. They also collect forest resources such as Mahua fruit, Tora fruit, Tendu leaves and Tamarind, which are vital income sources for tribal families, and engage in cattle rearing.

Parents often enrol their children in school as a formality, without lessening their work responsibilities. This trend likely arises from a limited understanding of education's value, particularly among parents with little or no education themselves.

This lack of emphasis on education creates a void of positive role models for kids currently in school. During my visit to Turkapara village, most children aspired to become “guruji” (teachers) or policemen—the most visible professions in the area. The absence of role models who have successfully completed their education compounds the issue, perpetuating the cycle of early dropouts.

Language barriers present a significant challenge, especially in South Chhattisgarh, where tribal languages are prevalent. These languages differ from Hindi, the medium of instruction in schools in the state, causing a gap in comprehension. Teachers often come from non-tribal, Hindi-speaking backgrounds, and may not be equipped to teach in the students’ native languages. In schools like the one I visited, where a single teacher manages all primary classes, children hesitate to ask questions. This further impedes understanding and diminishes interest in education.

Further, since many teachers are non-tribals, sometimes from outside the state, they may lack an understanding of the tribal culture and lifestyle. In certain instances, this ignorance manifests as discrimination against tribal students, intensifying their sense of isolation and hindering educational progress.

Geography

The rugged landscape and scattered communities further complicate school access for tribal children. During monsoon season, the journey involves navigating hills, ridges and streams. For instance, in Loha village of Dantewada district, the closest operational school is roughly 20 km away. Given these challenges, children frequently resort to attending government-run boarding schools, known as “ashram shalas.”

Conflict

In conflict-ridden areas like Sukma, the heavy presence of police and paramilitary forces puts civilians, including children, at risk. The ongoing strife has led to the damage, closure or abandonment of many schools. This discourages both students and teachers from attending, severely hampering educational access.

Shortage of Teachers

Teacher shortages exacerbate the issue, particularly in districts like Bastar and Sukma. Many schools fall below the state average in terms of staff numbers, and some even lack qualified teachers. This shortfall affects the quality of education offered.

Solution

Some potential solutions have been identified. Tribal societies have distinct lifestyles and traditions that are neither easily nor desirably changed. Activities like gathering forest produce and agricultural work are integral to their culture and are skills parents want to pass on. Expecting families to halt such practices is unrealistic.

However, educational policies could aim to make schools more accommodating for tribal children. For example, mainstream academic calendars often recognise holidays like Holi and Diwali, which are not typically celebrated by tribals. Yet, there are no designated breaks for tribal festivals or critical periods like the collection of Mahua or Tendu leaves. Adjusting the academic calendar to align with the tribal calendar could be a step toward making education more accessible and relevant for these communities.

The government has taken steps to improve education for tribal students. Initiatives like “ashram shalas” and “portacabin schools,” or portable schools, aim to tackle challenges related to inaccessibility and absenteeism.

The Standing Committee on Social Justice and Empowerment has noted problems like poor food quality and overcrowding in “ashram schools.” A recent incident involving a sexual assault on a six-year-old girl in an “ashram school” in Sukma has caused outrage among the tribal community.

It’s understandable that education is an unappealing option for parents and children, many of who are first-generation schoolers. However, the onus is on the government to do more to prevent educational dropouts in these communities. Hence, addressing the existing problems within the education system, and making the school curriculum more attuned to the needs and culture of tribal children, would significantly contribute to preventing them from abandoning their education.

Effective policy changes and improved school environments could make education more appealing and accessible for these families.