What Does Gandhi Have to Do with Cleanliness?

Let’s Focus on His Approach to Governance Instead

Newsreel Asia Insight #2

Oct. 2, 2023

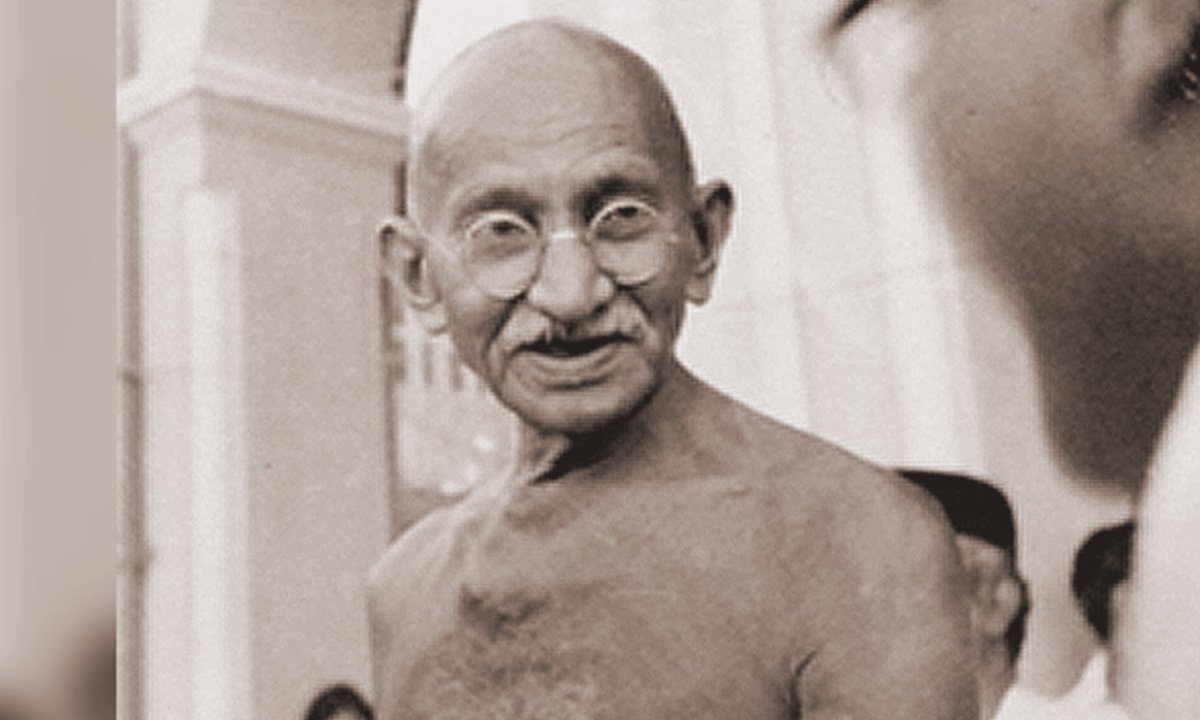

Cleanliness campaigns in India these days invoke Mahatma Gandhi, but the iconic leader’s vision for the country went far beyond sanitation. Gandhi’s writings and speeches reveal a broader mission that contrasts sharply with the current direction of Indian governance.

Mahatma Gandhi’s vision for India was rooted in the concept of Swaraj, or self-rule, which he described as “Ramarajya.” Gandhi clarified that Ramarajya was not a Hindu-centric term but a universal concept. “My Rama is another name for Khuda or God. I want Khudai raj, which is the same thing as the Kingdom of God on earth,” Gandhi said in a statement published in Haimchar on Feb. 26, 1947.

The idea of a Hindu Rashtra, which alludes to dominance of the majority and being called for by a section of society, sharply diverges from Gandhi’s vision of integrating Hinduism into governance.

Gandhi further elaborated that Ramarajya meant a society where inequalities based on possession, colour, race, or creed would vanish (The Hindu, June 12, 1945).

However, Oxfam India’s recent report, “Survival of the Richest: The India Story,” on wealth inequality reveals staggering disparities, as reported by The Indian Express. It shows that a mere 5% of Indians hold over 60% of the nation’s wealth. In contrast, the bottom 50% own just 3%.

It further highlights that from 2012 to 2021, 40% of the wealth generated in India went to only 1% of the population. Meanwhile, the bottom 50% received a paltry 3% of this wealth. The report also notes a significant increase in the number of billionaires, rising from 102 in 2020 to 166 in 2022.

Further, Gandhi’s Satyagraha movement, which arguably led to India’s independence in 1947, was also grounded in religious beliefs. The movement was characterised by passive resistance and Ahimsa, or non-violence.

“I contemplate a mental, and therefore, a moral opposition to immoralities,” Gandhi wrote in Young India on Oct. 8, 1925. Satyagraha had three core components: a just cause, effectiveness through peaceful means, and a focus on self-purification rather than judgment of others (Speeches and Writings of Mahatma Gandhi, G.A. Natesan & Co., 1933; Hind Samaj or Indian Home Rule, Navajivan Publishing House, 1958; Young India, May 29, 1924).

However, current developments in the country—such as social exclusion, violence against minorities and dissenters, and virulent hate campaigns—stand in stark contrast to the three values held by Gandhi’s Satyagraha.

Gandhi was pragmatic and open to evolving his views. “When anybody finds any inconsistency between any two writings of mine, if he has still faith in my sanity, he would do well to choose the latter of the two on the same subject,” he stated (Harijan, April 29, 1933).

The evolution of one’s beliefs and intentional flip-flopping are fundamentally different. Unfortunately, what we observe in today’s politicians is the latter. When was the last time a politician actually apologised?

Unlike some contemporaries who used religion to further worldly interests, Gandhi incorporated religious tenets into politics with a vision broad enough to include all communities. “Religion, in its broadest sense, governs all departments of life, including politics,” he said (Madras Mail, December 22, 1933).

Much like Gandhi’s contemporaries, many today continue to exploit religion—not by adhering to its tenets, but by actively contravening them. Their use of religion operates as a zero-sum game, requiring the exclusion of other communities.

As India marks Gandhi’s birth anniversary today, the spotlight is missing on his broader vision of Ramarajya and ethical governance.