Discovering the South Asian Identity

Stepping off the plane at Kathmandu Airport in Nepal, I felt a rush of anticipation. A sign with my name awaited me, and a van whisked me and fellow delegates off to a conference destined to reshape my perspective on South Asian unity. The venue, buzzing with energy, was our meeting ground.

My first encounter was with my counterparts from Pakistan. I’d always harboured a dream to visit their country, making this moment particularly stirring. We exchanged warm greetings and soon found ourselves at dinner, where I sat beside Saher Baloch and Jalaludin Mughal from Pakistan, along with Esther Dorn-Fellerman from Germany, a DW Akademie representative.

Our introductions were simple yet profound: “I am from India,” I said. “I’m from Pakistan,” Saher stated. Jalaludin humorously added, “And I’m from Kashmir!” Laughter filled the room, breaking any barriers of nationality.

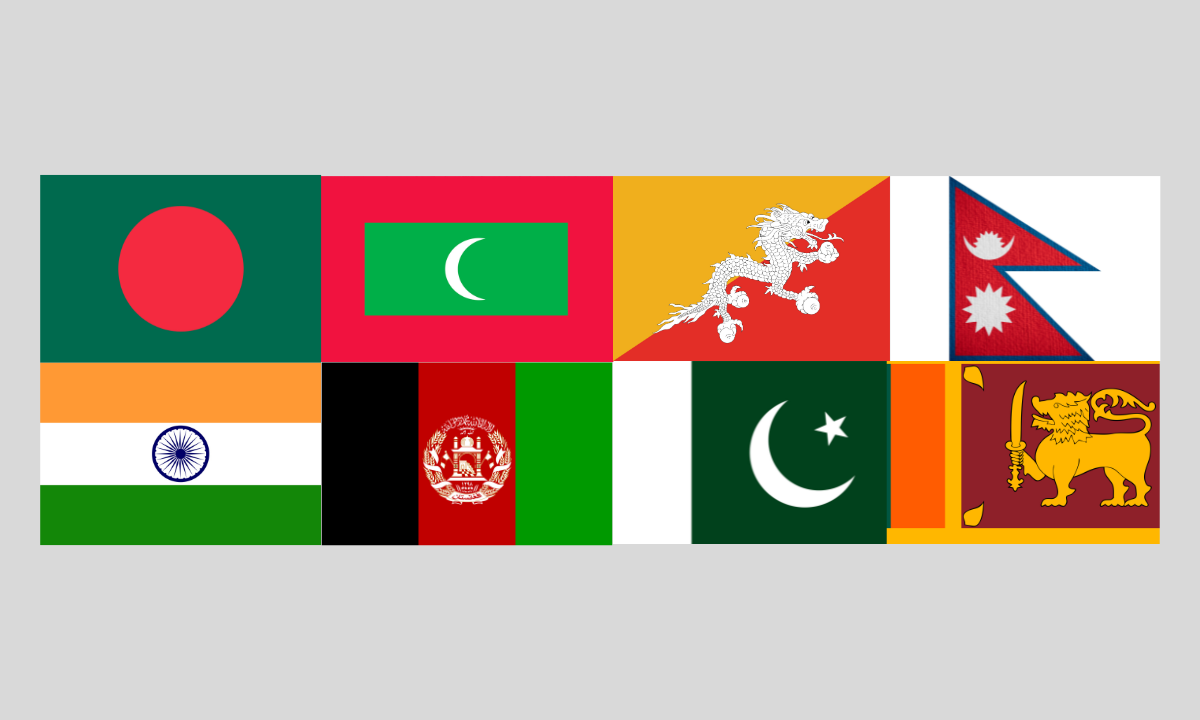

We had gathered for a three-day dialogue hosted by the South Asian Network for Communication, Displacement, and Migration (SAN-CDM), alongside the co-organisers Calcutta Research Group, DW Academia and Nepal Institute of Peace. The theme was “Connecting the Dots: Debating Displacement in South Asia,” and the attendance spanned the entire region.

Our dinner conversation meandered from the Palestinian-Israeli conflict to the plight of Afghans in Pakistan, and I shared insights into India’s caste-induced labour migration. Amid these heavy topics, we found lighter moments discussing music and cultural similarities.

In these exchanges, our national identities blurred into a shared South Asian consciousness. We spoke a common language of concern and empathy, momentarily forgetting our divided geographies. I learned of the travel constraints faced by my Pakistani friends, who couldn’t fly directly over Indian airspace, a stark reminder of the political barriers that fragment us.

Esther, observing our camaraderie, insightfully remarked that the India-Pakistan tension was more a governmental issue than a people’s problem. Her words resonated deeply, reinforcing my long-held belief.

The conference delved into the complexities of migration and displacement. Each story, whether from academia, journalism, or legal backgrounds, echoed universal challenges across South Asia. I was particularly struck by the migration trends in Nepal, where societal segments, regardless of class, were leaving the country.

Conversations with a local taxi driver and migration experts painted a picture of a nation in flux, with its people seeking greener pastures abroad or relocating internally due to unsustainable development and disasters.

The narratives from Bhutan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Afghanistan further underscored the regional migration patterns. From Bhutan’s brain drain to Sri Lanka’s crisis-driven exodus, and Bangladesh’s Rohingya refugee challenges, each story wove into a larger tapestry of shared struggles and aspirations.

My Pakistani friends brought to light various facets of migration in their country, from climate change impacts to the aftermath of regional conflicts. Saher’s accounts of the largely Shiite Hazara community’s plight and the desperation of those chasing foreign dreams were particularly poignant. Hazaras are considered to be one the most persecuted communities in the Sunni-majority Afghanistan.

Jalaluddin’s insights into Kashmiri refugees in Pakistan-administered areas highlighted the underreported aspects of displacement in that region.

“Connecting the Dots: Debating Displacement in South Asia,” held in Kathmandu in November 2023

My own presentation focused on India’s internal migration, a narrative of rural poor seeking respite from oppressive societal structures in urban landscapes. Yet, the heart of migration stories lies in the shared human experiences of separation, longing and the quest for a better life.

Migration and displacement emerged as key themes that could nurture this shared solidarity.

The migration patterns across South Asia have been shaped by significant international and internal movements, influenced by political, economic and sub-regional social developments, continuing to influence migration trends today. South Asia stands out as one of the primary regions of origin for international labour migrants, particularly destined for the Gulf Cooperation Council countries.

Being the world’s most populous country, India contributes the highest annual number of migrants globally, with 2.5 million people migrating overseas. In 2022, the number of individuals departing from Pakistan to go overseas reached 765,000, nearly triple the figure from 2021.

As per the 2021 Census Nepal Data, a total of 2.2 million Nepalis currently reside abroad, and over 1,700 individuals are leaving the country daily. In the early months of 2023, the recorded number of people leaving Bhutan was 5,000 a month, matching the net increase in the population — the difference between births and deaths — per year!

Nearly 43 million people from South Asia reside abroad, marking the sub-region as the global leader in emigrant numbers. Irregular migration, defined as movement occurring outside the regulatory norms of the sending, transit and receiving countries, is a frequent phenomenon within and from South Asia.

The Gulf economies depend significantly on the South Asian labour force, acting as a crucial pillar. Despite their pivotal role, these workers often find themselves compelled to seek out basic necessities, such as food, without the support of safety nets, social security protection, welfare mechanisms, or labour rights.

Recent reports indicate that the Israeli construction industry has requested permission from Tel Aviv authorities to hire up to 100,000 Indian labourers as substitutes for Palestinian workers. While their cost-effective labour is consistently welcomed, the question of whether they receive dignified treatment and assured safety remains uncertain.

Upon the conclusion of the conference, it became evident to me that our discussions surpassed political boundaries, revealing a profound sense of shared identity and solidarity. Our narratives, woven with both sorrows and joys, indicated a deeper connection—a shared South Asian identity that unites us in our collective human journey.

However, India has often preferred bilateral engagements over multilateral ones in South Asia, an approach that could be aimed at leveraging its size and influence. It leads to perceptions that India is not fully committed to fostering a unified South Asian identity, preferring instead to deal with neighbours individually on its terms.

A united South Asian identity can help the region grow together economically, especially helping smaller countries. This unity makes it easier for these countries to enter bigger markets and find new chances to grow. Also, it’s tough for smaller countries to make their voices heard worldwide. But, by coming together as South Asia, they can speak louder and make a bigger impact in international discussions.

Lastly, with big powers like China and the U.S. playing major roles in Asia, a united South Asia can better handle these outside influences.

This South Asian teamwork means the countries in the region can face big challenges more effectively together. This was evident in our Kathmandu gathering, showcasing the strength of collective effort.

(The opinions expressed within the content are the author's.)