Assam’s NRC Misstep: Court Demands Deportation of ‘Illegal Foreign Nationals’

State Government Admits Uncertainty Over Detainees’ Nationalities

February 5, 2025The Supreme Court has rebuked the Assam government for keeping people it has declared as “foreigners” in indefinite detention and for its slow pace in arranging their deportation. State officials claim they do not know where to send them. It exposes a fundamental problem rooted in the National Register of Citizens (NRC): if individuals are declared foreign solely because their documents are considered insufficient, what happens next?

On Feb. 4, Justice Abhay S. Oka, heading the bench, asked the state’s chief secretary, “You have refused to start deportation saying their addresses are not known. Why should it be our concern? You deport to their foreign country. Are you waiting for some mahurat (auspicious time)?” as quoted by The Telegraph.

In Assam, the NRC is an official list intended to separate people deemed legitimate Indian residents from suspected undocumented migrants, particularly from neighbouring countries, like Bangladesh. First prepared in 1951, it was updated under Supreme Court supervision, requiring residents to submit documents such as birth certificates and land records to prove their lineage. In the 2019 update, around 1.9 million individuals were excluded, prompting concerns about bureaucratic errors and the possibility that genuine citizens could be wrongly classified. Of these, 500,000 (5 lakh) were Bengali Hindus, and 200,000 (2 lakh) were caste Assamese Hindus and sub-groups, according to Maktoob Media. They risk detention or deportation if the authorities decide their documents are insufficient to prove they are Indian.

As part of the NRC process, there are 63 foreign nationals slated for deportation, according to the Assam government. However, this has not been possible because the government cannot determine their nationalities or the addresses.

Lawyer Colin Gonsalves, who is representing a “foreign” national, told the bench, “My information is that attempts are being made by the government to figure out if Bangladesh will take these people out. Bangladesh is refusing. India says they are not Indians. Bangladesh says they are not Bangladeshis. They have become stateless. They are in detention for 12-13 years. Bangladesh says they won’t accept anyone who lived in India for many years.”

The case involves 270 individuals currently detained in detention centres and transit camps in Assam.

Advocate Shadan Farasat, also representing a detainee, told the bench that his client, a Bengali from Bengal, had been detained for eight years. He explained that his client could not be released on bail from the detention centre because his wife had disowned him and abandoned their matrimonial home.

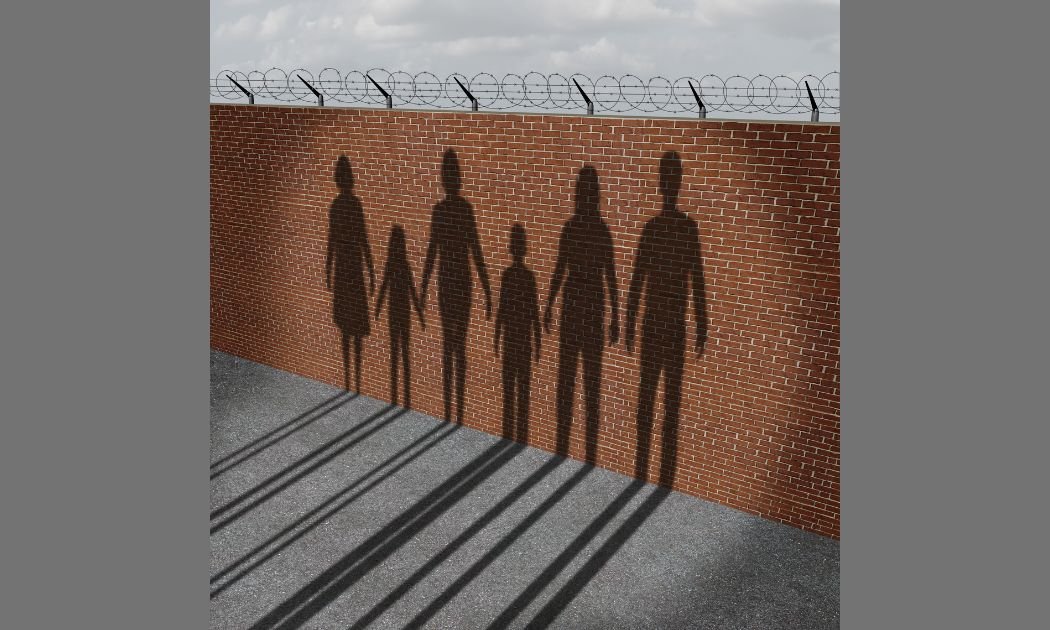

No practical plan seems to have been made for dealing with individuals categorised as non-citizens when those individuals cannot produce what the government calls valid identity records. So, while the NRC exercise has created a legal basis to call some people “foreigners,” the state finds itself stuck when it comes to actually sending them anywhere.

It’s like a system meant to protect the integrity of citizenship records can instead trap individuals in seemingly endless detention.

Lawyers for the detainees told the Supreme Court that people declared foreign may remain stranded if no nation accepts them. Meanwhile, the Assam government covers the cost of round-the-clock detention, which the court has flagged as a drain on public funds.

What’s surprising is that despite this flaw, proposals have surfaced to replicate the NRC on a national scale.