Three Reasons Why the Violence Persists in Manipur

And the First Step Towards Stopping It

By Vishal Arora

Commentary

Jan. 23, 2024

The mass burial of around 87 bodies of Kuki-Zo people killed in the violence was held in December 2023. Photo by Vishal Arora

A recent incident in Manipur’s Moreh town, where houses and schools were allegedly set ablaze by Manipur Police commandos, illuminates three primary reasons for the ongoing ethnic violence, which has persisted for over eight months. It also offers insights into the first steps required to cease the unrest.

Amid the conflict between the majority Meitei community of the Imphal Valley and the Kuki-Zo tribal people from the hill districts, CCTV footage implicated uniformed individuals, believed to be Manipur Police commandos and members of the Meitei extremist group Arambai Tenggol, in the arson on Jan. 17. These police commandos, forming a special unit within the police department, were seen setting fire to several houses, schools, and the premises of the Moreh Christian Assembly Hall, as reported by ThePrint.

The footage also corroborated allegations made by local residents that personnel from the Assam Rifles, a central force, stood by as men in uniform entered the area and committed acts of arson, according to the news report. The incident was apparently in retaliation for the killing of two state police commandos by suspected Kuki-Zo militants, as reported by The Economic Times.

ThePrint reported that Myanmar’s fire department, a foreign agency, played a crucial role in extinguishing the blaze, highlighting the state government’s failure to manage the crisis effectively.

Now, let’s quickly understand the context of the violence.

Since May 3, 2023, the state has been engulfed in turmoil. At least 158 Kuki-Zo individuals have been killed, tens of thousands remain displaced, and significant property destruction has occurred, according to the Indigenous Tribal Leaders’ Forum.

The violence ensued following a directive from the Manipur High Court to the state government, contemplating the possibility of allowing Meiteis to buy land in Kuki-Zo territories. This decision ignited protests among the tribal communities, which rapidly escalated into widespread violence, fuelled by disinformation and extremist rhetoric.

However, the conflict is not solely about ethnic or political differences. It is also deeply rooted in economic interests, particularly in the resource-rich Kuki-Zo areas. The government’s interest in these lands, especially under the Bharatiya Janata Party since 2017, has led to policies threatening Kuki-Zo land ownership and livelihoods.

Kuki-Zo women at a protest in Churachandpur, Manipur. Photo by Vishal Arora

Now, let’s examine the three primary reasons for the ongoing violence.

One: The state government appears to be siding with the Meiteis.

The Manipur Police, dominated by Meiteis, has been consistently accused of complicity since the violence erupted on 3 May 2023, as reported by media outlets including The Guardian, The Wire, The News Minute, and Newsreel Asia.

In August 2023, about three months after the violence began, the Supreme Court noted: “The slow pace of investigation by the investigating machinery in the State of Manipur has emerged from the material which was placed before this Court which is indicative of: a. Significant delays between the occurrence of incidents involving heinous crimes including murder, rape, and arson and the recording of zero FIRs; b. Significant delays in forwarding the zero FIRs to the police stations which have jurisdiction over the incidents; c. Delays in converting the zero FIRs into regular FIRs by the jurisdictional police stations; d. Delays in recording witness statements; e. Lack of diligence in recording the statements under Section 161 and Section 164 CrPC; f. The slow pace of effecting arrests in cases involving heinous offences; and g. The lack of urgency in ensuring medical examination of victims,” as reported by LiveLaw.

Moreover, government data indicates that since the violence began, around 5,600 weapons and 650,000 rounds of ammunition have been stolen, predominantly by the Meiteis, from the Manipur police, according to The Indian Express. These weapons were likely used in attacks against the Kuki-Zo people. The inability of armed policemen to prevent such a significant theft is difficult to comprehend.

Therefore, the situation does not appear to be a simple clash between two communities with the state government acting as a neutral party. If this were the case, the violence would likely have been contained within days. Instead, it seems to be a series of violent acts directed at the Kuki-Zo people by Meitei extremist groups, with the state government, particularly its police department, providing not-so-tacit support. This complicity is the main reason for the continued violence, despite the deployment of over 40,000 security personnel from central forces, including the Indian Army, Assam Rifles, Central Reserve Police Force, and Border Security Force.

Meiteis have also been casualties in the conflict, but mainly as they ventured into Kuki-Zo villages near Meitei areas to launch attacks. These Meitei assailants met resistance from Kuki-Zo “village volunteers” – armed youths defending their communities in Churachandpur district and other Kuki-Zo regions in Manipur.

Personnel from the Indian Army look at a burnt car in Imphal, Manipur. Photo by Vishal Arora

Two: Partial enforcement of the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, or AFSPA.

The challenge for the central forces stems from the fact that law and order is a state responsibility, as outlined in the Indian Constitution. Consequently, despite being aware of the police's bias, they cannot take full control of the situation.

Interestingly, AFSPA, which grants enhanced control to central forces and implemented in Manipur in 1980, is currently predominantly in force in tribal areas rather than in regions where Meiteis form the majority.

In April 2022, AFSPA was lifted from 15 police station areas across six districts. Furthermore, about a month before the violence began, on 1 April 2023, the “disturbed area” notification was withdrawn from an additional four police stations. And in late September 2023, the state government issued a notification to maintain the status quo for another six months beginning October 2023, The Hindu reported.

In areas not declared as “disturbed” but still experiencing violence, the role of the central armed forces is limited and supportive; they may be deployed to assist local police and state law enforcement agencies in maintaining law and order. Their role, in that case, is often to provide additional manpower and resources during times of crisis or heightened tension. In disturbed areas, the central armed forces can conduct independent operations without needing direct orders or permission from local police.

This overlooks the nature of insurgencies in Manipur and the changing context after the May 2023 violence began. Despite its controversy, implementing AFSPA across Manipur seems appropriate given the current circumstances.

The valley-based insurgency, driven by the Meiteis’ desire for independence or autonomy, began with Manipur’s incorporation into India in 1949. The 1980s and 1990s saw heightened activity by valley-based insurgent groups, leading to government countermeasures and the implementation of AFSPA. Some militant groups from the Valley fled to Myanmar, with reports indicating that some have since returned to the Valley months after the violence started in May 2023.

The Kuki-Zos, on the other hand, sought a separate state within India. In 2008, Kuki-Zo groups entered into an agreement with both the central and Manipur governments, known as the Suspension of Operation.

Regarding the Moreh arson incident, sources from Assam Rifles refuted the allegation that its personnel remained passive spectators, as reported by ThePrint, which also quoted a source stating that the force’s involvement is limited to the extent permitted by its “mandate.” It was likely a reference to AFSPA.

As for the killing of two police commandos in Moreh, the presence of Meitei police officers and constables was seen as a major provocation by the Kuki-Zo people and groups. Kuki-Zo women organised a sit-in protest following the arrival of additional Meitei policemen, who were deployed via helicopter during the night in mid-October despite peace prevailing in the area and an already heavy presence of central armed forces at the time, as reported by The Hindu.

In early November, all 10 Kuki-Zo Members of the Manipur Legislative Assembly, including eight from the ruling BJP, accused the state police of molesting women and assaulting people from their community in Moreh, as reported by Scroll.in.

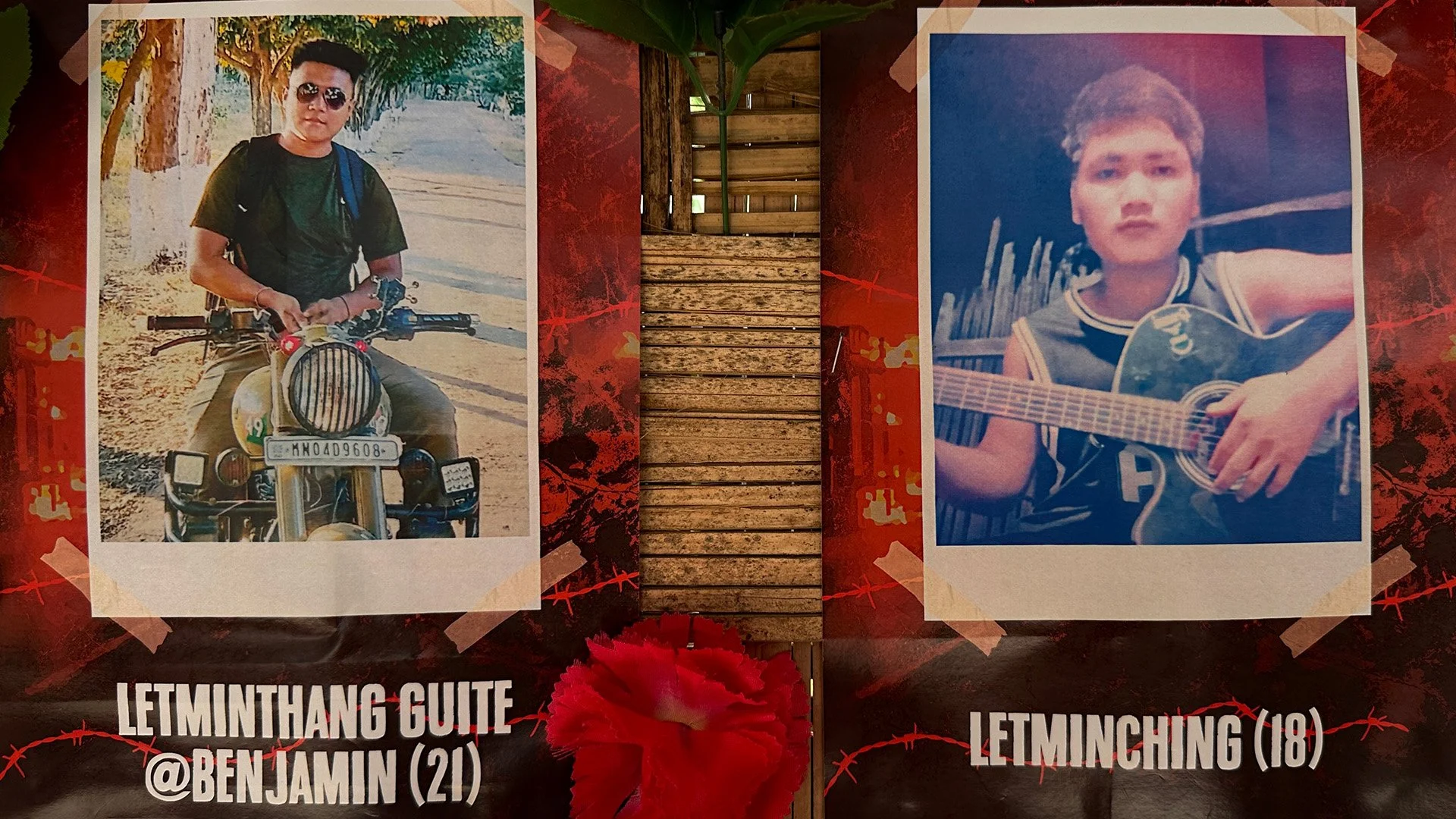

Images of two Kuki-Zo youngsters killed in the Manipur violence. Photo by Vishal Arora

Three: The central government, as the sole potential mediator, is postponing the necessary tough decision.

The central government, led by the BJP, has been criticised for not exerting enough pressure on the Manipur state government, also ruled by the same party, to stop the violence.

Initially, the central government seemed to disregard the state government’s involvement in the unrest. However, the central government’s stance likely shifted towards pressuring the state following the widespread sharing of a video in July 2023, which showed two Kuki-Zo women being paraded naked by a group of Meitei men. By then, it might have been too late. Weeks earlier, Manipur Chief Minister Biren Singh had announced his intention to resign, only to later reverse his decision, citing community pressure to stay in office – a move opposition parties described as a chair-saving drama, as reported by The Hindu.

Mr. Singh’s alleged strong popularity and support among the Meitei population in Manipur at the time may have exceeded the central government’s control. Taking action against Mr. Singh could provoke significant opposition from the Meitei community. Consequently, the central government apparently faced a difficult decision: either to allow the current situation to continue or to intervene with military force, risking high civilian casualties and fatalities. The latter option is undeniably undesirable, yet granting greater control to central forces might be the first step towards restoring peace.

Under AFSPA, the central government has the authority to declare an area within a state as disturbed, even without the state government’s recommendation, if it deems it necessary for maintaining public order or for dealing with insurgent activities.

In addition to prioritising the saving of lives, which should be the foremost concern, the central government also has a compelling national security reason to take action.

While Mr. Singh may appear to maintain control in relation to the Meitei community and its various factions, there is a possibility that valley-based insurgent groups, which now seem to have garnered support among the Meiteis amid the ongoing violence, might revolt against him. Disillusionment with Mr. Singh is emerging, even among some civilian groups. For instance, according to The Sangai Express, Th Sujata, the convenor of Imagi Meira, a women’s organisation, recently labelled him as “weak.”